Introduction

GIN (Generalized Invertes Index) indexes are often used to index arrays, jsonb, and tsvector (for fulltext search) columns.

When it comes to array, they are, for example, used to verify if an array contains an other array or elements (the <@ operator).

In the documentation you can see the full list of operators.

But the question that I want to answer in this article is: “why should we use GIN indexes for this data types and operators ?”

I’m going to go over two examples, one for arrays and one for fulltext search.

Before going further, I’ll probably talk a lot about BTrees, so you would probably benefit from reading my blog post about their structure.

So now, the plover birds want to have, for each crocodile, the list of teeth that they had to heal. Because it is much simpler when they see again the crocodile to just know which teeth could be more fragile, and I mean, they see a lot of crocodiles every day, plover birds don’t have an elephant memory.

So I added a new column healed_teeth, an integer array (integer[]). So if I take a totally random crocodile, I’ll have:

croco=# SELECT email, number_of_teeth, healed_teeth FROM crocodile WHERE id =1;

-[ RECORD 1 ]---+--------------------------------------------------------

email | louise.grandjonc1@croco.com

number_of_teeth | 58

healed_teeth | {16,11,55,27,22,41,38,2,5,40,52,57,28,50,10,15,1,12,46}

And then I created the following index:

CREATE INDEX ON crocodile USING GIN(healed_teeth);

As for fulltext search, in this new updated version, crocodiles can give their symptoms to help plover bird know what’s wrong.

So I added a column symptoms to the appointment table. As we index tsvector, I also added a symptoms_vector column.

croco=# ALTER TABLE appointment ADD COLUMN symptoms text;

ALTER TABLE

croco=# ALTER TABLE appointment ADD COLUMN symptoms_vector tsvector;

ALTER TABLE

I filled the symptoms with some random dentistry related words that I found on this website. So now I have records looking like this.

croco=# SELECT * FROM appointment WHERE symptoms IS NOT NULL ORDER BY id LIMIT 10;

-[ RECORD 1 ]---+-------------------------------------------------------------

id | 12809

crocodile_id | 1

plover_bird_id | 21970

emergency_level | 7

done | f

area | 0101000020E61000000000000000005CC000000000000032C0

schedule | ["2015-01-03 17:49:00+01","2015-01-03 18:49:00+01")

symptoms | nozzle, syringe, gingivitis, acute necrotizing ulcerative (ANUG),

cornification, globular (adj), loss of primary teeth (SEE shedding

of primary teeth), muscle, canine, wear, occlusal, stricture,

vitrodentine, apposition, hazard, radiation, system, nervous,

sympathetic, eleidine

symptoms_vector | 'acut':4 'adj':10 'anug':7 'apposit':26 'canin':21 'cornif':8

'eleidin':32 'gingivit':3 'globular':9 'hazard':27 'loss':11

'muscl':20 'necrotizing':5 'nervous':30 'nozzl':1 'occlusal':23

'of':12,17 'primary':13,18 'radiat':28 'se':15 'shedding':16

'strictur':24 'sympathetic':31 'syring':2 'system':29

'teeth':14,19 'ulcer':6 'vitrodentin':25 'wear':22

(These crocodiles have much more dentist vocabulary than me…). And then I created a GIN index on the symptoms_vector column.

CREATE INDEX ON appointment USING GIN(symptoms_vector);

GIN structure

The structure of a GIN index is close to a BTree index. There are a few differences that we’re going to be exploring right now.

Metapage

As for a BTree Index, the first page of a GIN index is the metapage containing information about the index. The difference being the information that is slightly different. For example in a GIN index you won’t find any fast root.

You can see the metapage information using the postgres extension pageinspect

croco_new=# SELECT * FROM gin_metapage_info(get_raw_page('crocodile_healed_teeth_idx', 0));

-[ RECORD 1 ]----+-----------

pending_head | 4294967295

pending_tail | 4294967295

tail_free_size | 0

n_pending_pages | 0

n_pending_tuples | 0

n_total_pages | 358

n_entry_pages | 1

n_data_pages | 356

n_entries | 47

version | 2

n_total_pages: indicates the total number of pages in the index (see the introduction article if you’re not familiar with pages)n_entry_page: the number of entry pagesn_entries: the number of entries in the indexn_data_pages: the number of data pages

In a GIN index there are two types of pages. The entry pages and the data pages.

- The data pages are the pages inside a posting tree (see the leaves paragraph.

- The entry pages are the pages containing the values in the index.

Both types of pages have opaque data containing:

- a flag to define the type (leaf, data, compressed, meta)

- the right sibling

- maxoff ?

Entries

The keys (entries) in a GIN index are stored in entry pages in the form of a binary tree.

Until now, this all is very close to a BTree index. Indeed the first page of the index is the metapage, and then the keys are stored into a binary tree.

There are some major differences though…

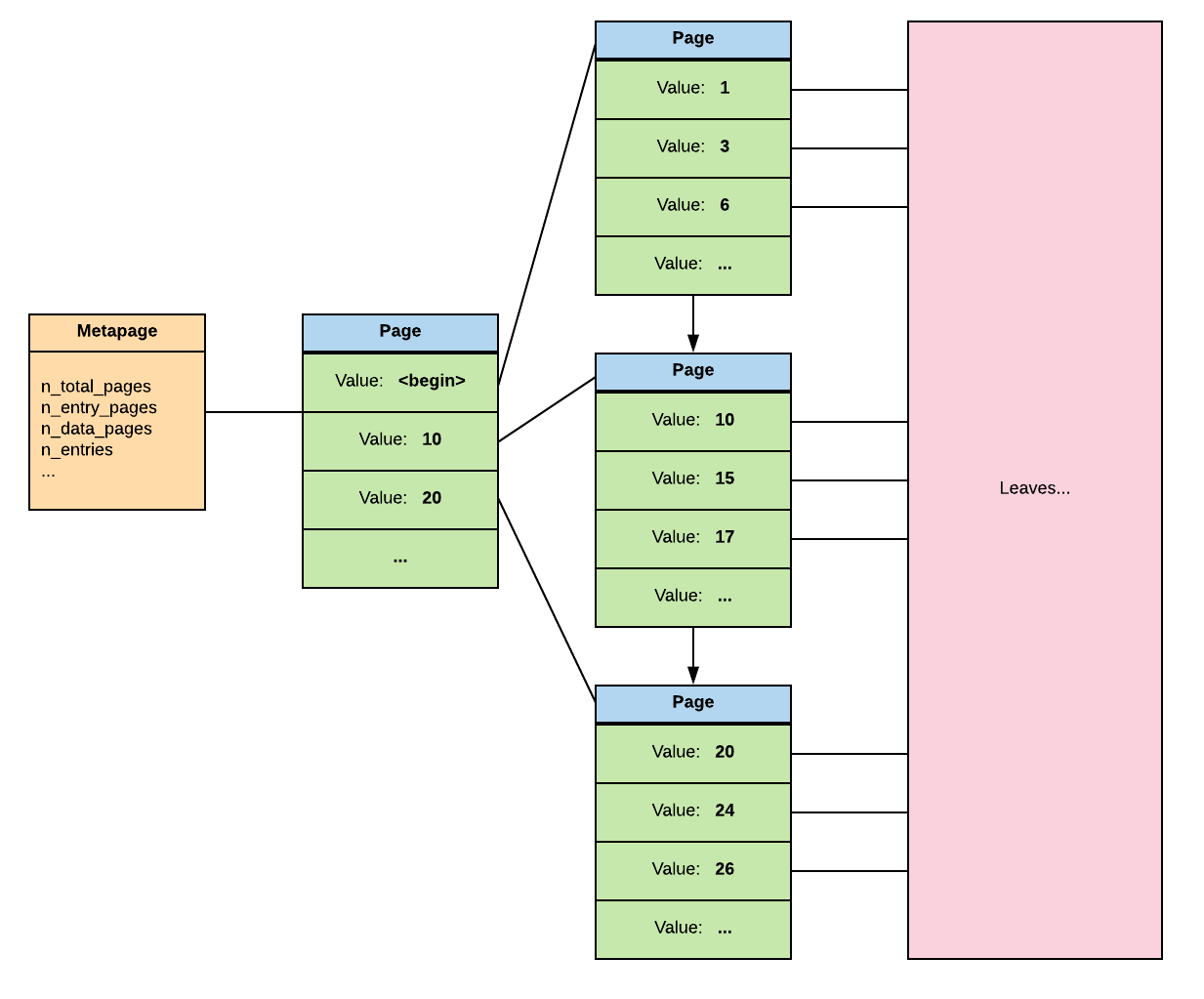

First, if you were indexing an array in a BTree index, the values would be directly the array. So your BTree would look something like that

Let’s say we would like to have all the crocodiles who ever had their first and second teeth healed. Here would be the query giving us this result.

SELECT email FROM crocodile WHERE ARRAY[1, 2] <@ healed_teeth;

I dropped the GIN index and here is the result of the EXPLAIN.

Seq Scan on crocodile (cost=0.00..9462.04 rows=54786 width=29)

(actual time=0.021..158.544 rows=73275 loops=1)

Filter: ('{1,2}'::integer[] <@ healed_teeth)

Rows Removed by Filter: 250728

Planning time: 0.157 ms

Execution time: 161.716 ms

(5 lignes)

It’s using a sequential scan and not the index, which means that it’s scanning the entire table to find the rows matching the WHERE clause.

In a GIN index, the array is split and each value is an entry. Which means that for the row with healed_teeth being {1, 6}, there will be an entry for 1 and for 6.

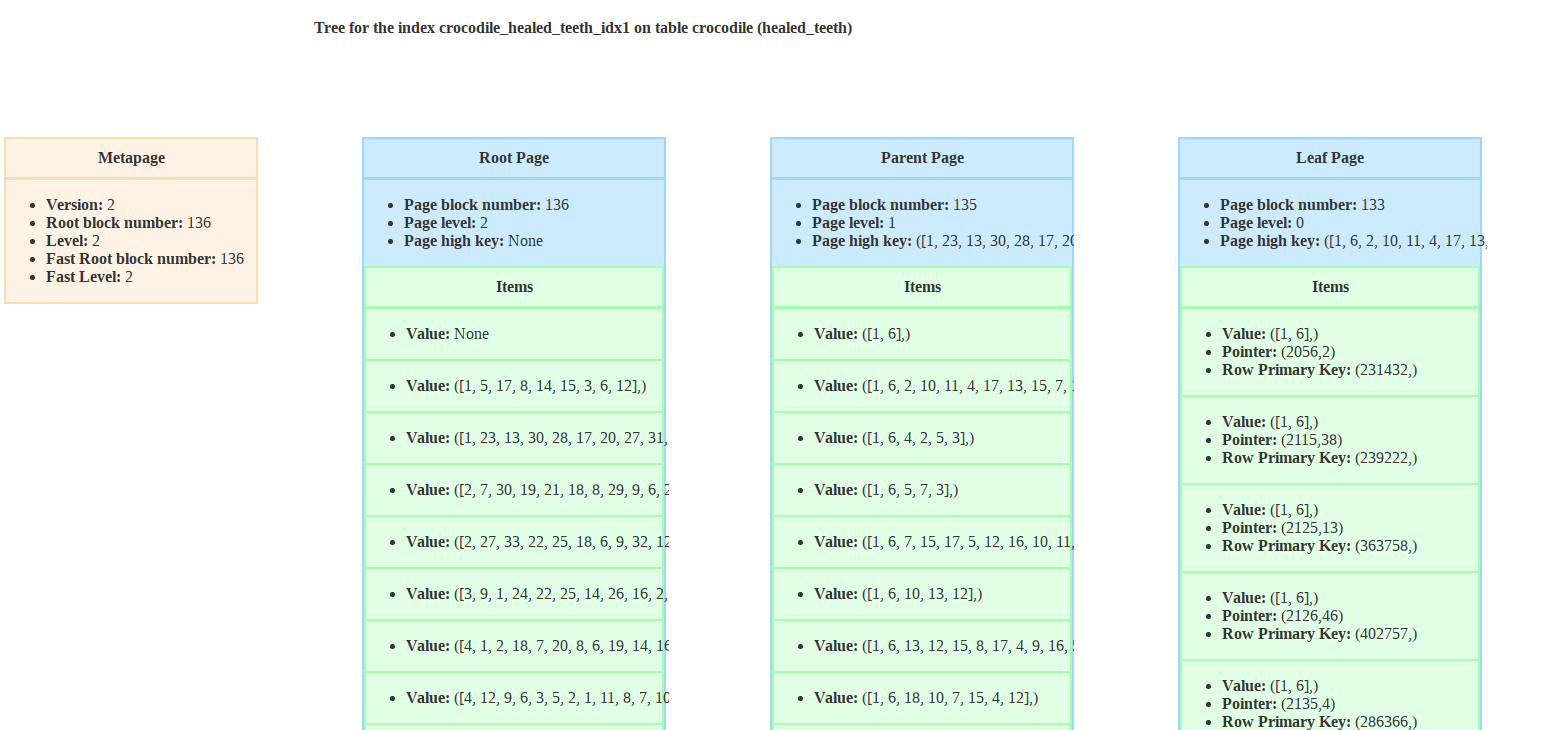

So the BTree on the parent level (we’ll talk about the leaves in a bit) of the GIN index for the healed_teeth would be like this.

We can here note that unlike in a BTree, the pages in a same level only have a right link instead or right and left.

So, each value of a list being indexed, it becomes easy to find which crocodiles have the teeth 1 and 2 healed. And as you can see in the following explain, the index is used.

Bitmap Heap Scan on crocodile (cost=516.59..6613.42 rows=54786 width=29)

(actual time=15.960..38.197 rows=73275 loops=1)

Recheck Cond: ('{1,2}'::integer[] <@ healed_teeth)

Heap Blocks: exact=4218

-> Bitmap Index Scan on crocodile_healed_teeth_idx (cost=0.00..502.90 rows=54786 width=0) (actual time=15.302..15.302 rows=73275 loops=1)

Index Cond: ('{1,2}'::integer[] <@ healed_teeth)

Planning time: 0.124 ms

Execution time: 41.018 ms

(7 lignes)

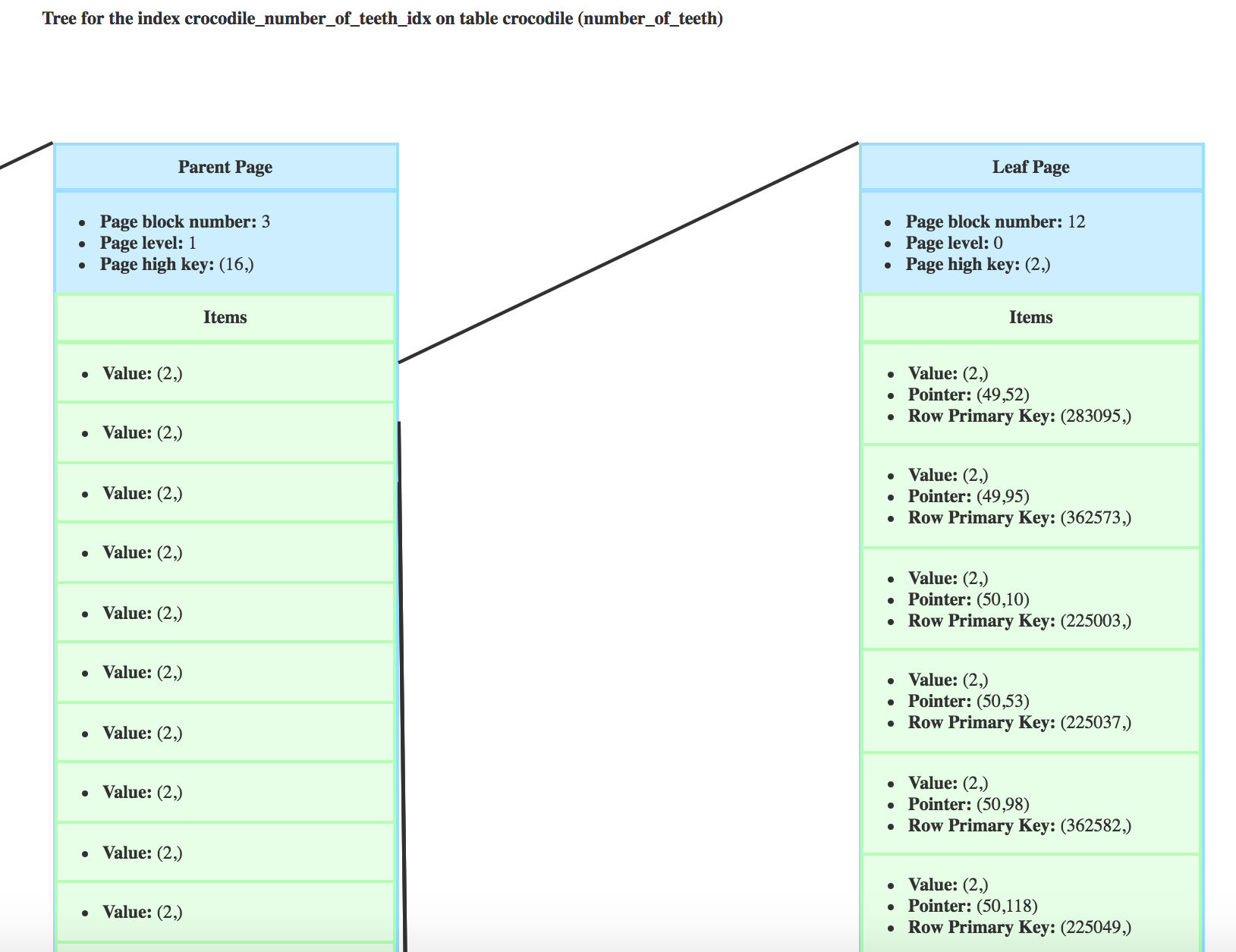

The second difference is that the values are unique in a GIN index.

In a BTree you could have several items with the same value. It’s the tuple (value, pointer) that in a BTree insures the uniqueness of the index entry.

The uniqueness of the values make it so that a GIN index is optimized for cases where the same value appears in many different rows.

Leaf pages

In a BTree index, on the leaf level, there is as many items as rows. So a same value can be repeated several times like you can see in the leaf level of the index on the number of teeth of the crocodile

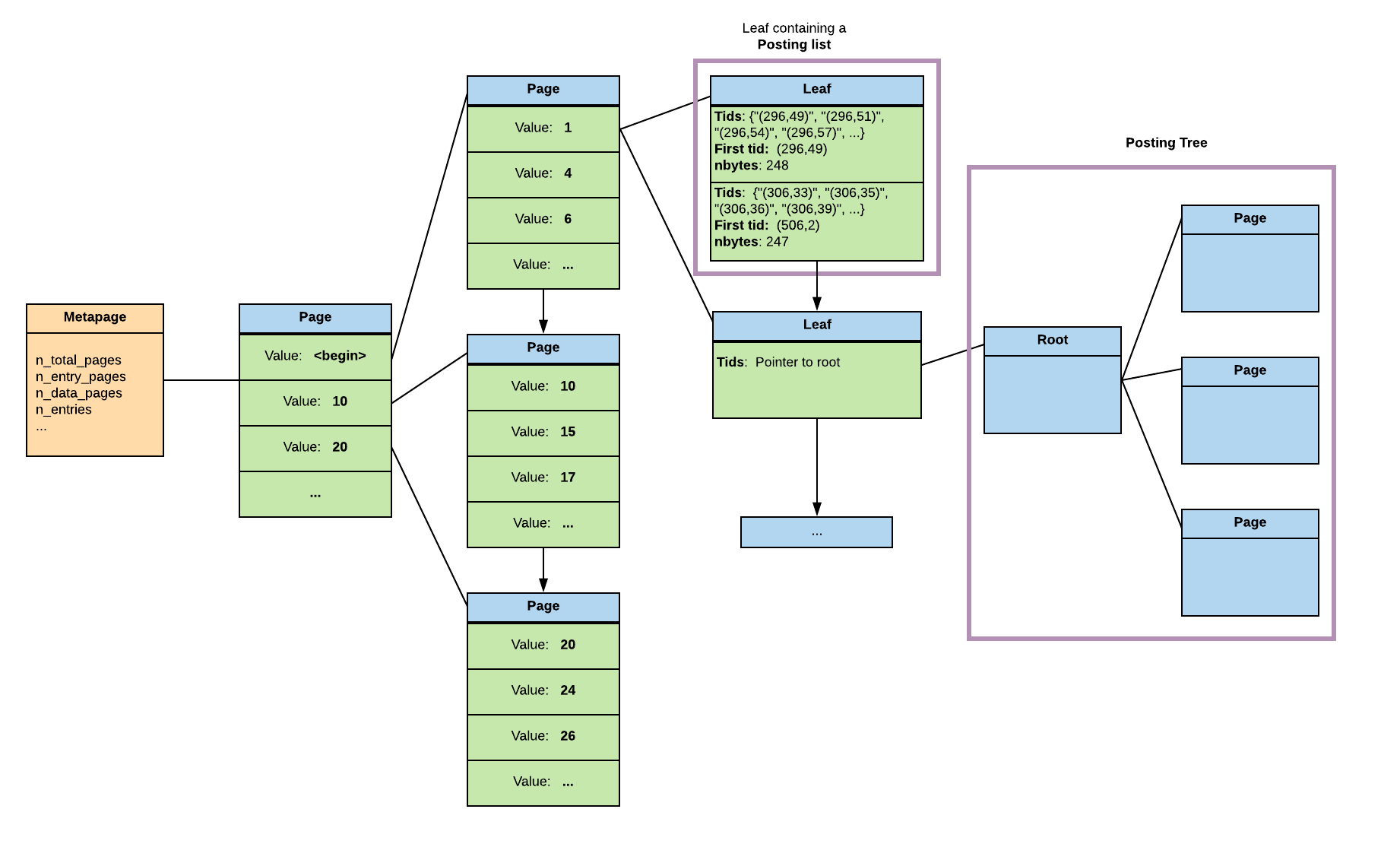

As I said earlier, the entries are unique in a GIN index. So the leaf levels contain either a list or a tree of pointers to the rows.

Posting list and posting tree

In a leaf page, the entries contain a list called posting list of item pointers in a compressed format.

If the list becomes to big so the item can’t fit anymore in the index page, the posting list is splited into different pages that are organised as a BTree. That’s what is called a posting tree. In the leaf item is stored a pointer to this tree instead of the posting list.

The pointers to the heap in a posting list are stored in physical order. In a posting tree the pointers are the keys.

So now that we’ve talked about the leave, here is what a GIN index looks like with its levels :)

The pending list

Inserting new rows in a GIN index is quite slow. I will talk about the insert algorithm a bit later, but to sum it up, because of the unicity of the values, an insert is slower than inserting in a normal BTree, indeed the posting list or tree have to be updated.

In order to optimise inserts, we store the new entries in a pending list which is a simple linear list of pages. Once the pending list reaches its limit or there is a VACUUM, the entries are moved to the Btree using a bulk insert which is optimised especially if there are multiple rows for each value.

The pending list limit can be set index by index (see the documentation) or globally with the configuration parametter gin_pending_list_limit.

The downside of the pending list is that when searching in a GIN index, the BTree and the pending list have to be scanned.

If you’re in a case where your data rarely changes and you don’t care about the update being slow, you can disable the pending list by setting fastupdate to false either when you create the index of by using ALTER INDEX.

If you’re using ALTER INDEX the pending list won’t automatically be flushed, so you might need to call VACUUM on your table to ensure that all data are moved to the BTree.

To sum up

To sum up, a GIN index has:

- A metapage

- A BTree of key entries

- The leaves either contain a pointer to a posting tree, or a posting list of heap pointers

- The pointers are ordered in physical memory order, in the posting tree, it’s the tid that is used as a key to build the tree

- The rows that are not in the index yet are in a pending list

Searching in a GIN index

When postgres uses the GIN index, you’ll notice in the EXPLAIN that it’s always doing a bitmap heap scan. It means that the search algorithm returns a map of tids (pointers to rows) in physical memory order.

Considering the way the data is stored inside the posting lists and trees, it makes a lot of sense to use this method.

The function that performs the search and builds the bitmap is gingetbitmap.

Step 1: scan keys

As for the search in a BTree, scan keys are used.

So the first thing that this function does is to initialise the scan keys.

- free previous scan keys,

- init scan keys

Step 2: Scanning the pending list

As I said earlier, when looking into a GIN index, the pending list and the main BTree have to be scan. This step concerns the pending list.

scanPendingInsert does that.

- First, the metapage is locked. This lock prevents from changes in the pending list (in case of fast insert where rows would be added or VACUUM that could empty the list)

- We get the block number of the head of the pending list. If the block number is not a valid one, it means that there is no pending list. The locks can be dropped.

- Then the list is fetched into a

pendingBuffer. Once the buffer is set, we can now drop the previous locks. - For each row, if the row matches all scan keys, it is added to the bitmap using the funciton

tbm_add_tuples

Step 3: scanning the main index

The function startScan is called to scan the main tree of a GIN index.

The first thing that does is to search for the entries that appear in the scan. For that it’s using the function GinFindLeafPage for each entry. This is (again) close to the behaviour in a BTree, the main BTree is traversed, until the leaf where the entry could be found. If necessary, the posting tree has to be explored as well to retrieve the TIDs.

The next step is to actually match the scan keys. If the scan key only has one entry, no other work is necessary, we already found the TIDs matching the scankey.

This is the case for example if I search for the appointments that were for crocodile with caries.

croco_new=# SELECT COUNT(*) FROM appointment WHERE symptoms_vector @@ to_tsquery('caries');

count

-------

35859

(1 ligne)

But let’s say one of the plover birds is doing a research to find the appointments for crocodiles with caries and that had osteoplasty.

In the database I have 35859 appointments with the syndrom description containing the word carie, and only 501 with the word osteoplasty.

So the query to find the appointments is:

SELECT * FROM appointment

WHERE symptoms_vector @@ to_tsquery('osteoplasty & caries');

So first the search algorithm finds the leaves pages for the entries osteoplasty and carie.

But the scan key in this case is a AND. So finding the entries is not enough to match the scan key.

The function startScanKey optimises the match by deviding the entries into two categories, the required ones and the additionnal ones.

To do that, first the entries are ordered by frequency. In my case, caries is more frequent than osteoplasty. Postgres then tries to put as many frequent entries as possible in the additional entries.

So here my required set would contain the entry osteoplasty, and the additional one the entry carie. Thanks to that, we can take the items matching osteoplasty, and when going over the items matching carie, we can just skip any TIDs that wasn’t already in the osteoplasty entry. As there are 501 appointments with osteoplasty and 35859 for caries, this optimisation is very interesting.

Step 4: updating the bitmap

Once we retrieved from the main tree the items matching the scan keys, we want to update the bitmap. Indeed, there are already elements in it coming from the pending list.

To sum up

In order to search in a GIN index,

- First the pending list is explored and a bitmap created with the matching rows

- Then the entries are searched in the main GIN structure

- If the scankey had a single entry, we have the TIDs of the matching rows

- Else, we need to find the right items matching the scan key. The use of required and additional entries helps with the optimisation of this step.

- Finally the bitmap is updated

Inserting in a GIN index

There are two ways data is inserted in a GIN index

Either fastupdate is set to true and the pending list is updated and the rows are moved from the list to regular GIN structure.

Or fastupdate is set to false and for each insert the tree is updated.

First let’s talk about fast update.

Updating the pending list

ginHeapTupleFastInsert: write the tuples to be inserted in the pending list.

- Checks if the tuples should be in a new list. For that it checks if the tuples fit in one page, if there is already a pending list and if there is enough space in the last page of the pending list to put the new tuples. If any of these three condition fails, the function

makeSublistis called If needed the pointer to head and tail of the pending list (in case of a new page) in the metapage are updated

If no new page, the tuples are simply inserted in the tail page

Inserting in the leaf

ginInsertCleanup -> move data to GIN structure. It calls GinEntryInsert with the list of tuple with the say key.

Once the data in moved to the main BTree, we reclean the one that might have been added during the clean up, and then mark the page as deleted. Deleting the data from the pending list after inserting makes it crash safe.

The function GinEntryInsert can be called with a list of tids or with a single onefor a key. This function is used for fastupdate and for “normal” insert.

The function finds the right leaf page using GinFindLeafPage where the entry should be inserted.

If the value is already in the main BTree, it means that the posting tree or posting list has to be updated.

Updating a posting list can be tricky (addItemPointersToLeafTuple). First, the list is updated and compressed. If the size of the list reaches the GinMaxItemSize, a posting tree has to be created.

In this case, the function GinEntryInsert calls createPostingTree with the pointers that were in the posting list. As they are already in order, it makes it faster to create the posting tree.

If the value wasn’t in the main BTree, the function buildFreshLeafTuple is called to add a leaf tuple in the current leaf page with a posting list (or tree) containing the new items. This might lead to a page split. To know more about page split, you can refer to the previous article as the page splits here are very similar.

Recursing to the parents

If a new tuple had to be inserted in a leaf page and it led to a page split, the parent needs to be updated to contain the downlink to the new page. I’m not going to go into much details here as this is quite similar to the behaviour in a BTree.

If you want to have fun you can look into the source code of the function ginPlaceToPage that recursively inserts in the parents and handles the page splits.

To sum up

Inserting in a GIN index can be in 2 or 3 steps.

- If

fastupdateis set to true: the new tuples are inserted in the pending list - Once the pending list is full, or there is a VACUUM, or

fastupdatewas set to false, the tuples are inserted in the main GIN tree. To do that:

- We look for the right leaf page to update

- If the value is already in it, the posting list or tree is updated

- Else a new item is inserted in the leaf, and if a page split occured, it recurses back to the parent.

- We look for the right leaf page to update

So basically, the only big difference with a BTree in this algorithm is the pending list and the insert in the leaves as the values are unique in a GIN index. This is also what slows inserts. I would probably advise you to use fastupdate (with a proper use of vacuum) as it will help have better write performances. But it really depends of your use case.

In my story, crocodiles are going to have tooth ache and come to ask for an appointment, describe their syndrom etc. thousands of times a day (not each croco though), so it would make crocodiles very angry to have to wait for the GIN index to be updated. And I mean, crocodiles are not the animal you want to mess up with…

Deleting from a GIN index

file ginvacuum

- A page from a posting tree has to be deleted

- Update the posting list, delete single pointer

- An item has to be deleted from leaf (no more pointer to this value)

Conclusion

The GIN index has a really interesting structure. I think that the most important part is to understand that the values indexed are split to get the keys. It’s the reason why it’s very efficient for fulltext search, arrays and jsonb.

But there are also some extensions for integers for example. It could be interesting if you want to index a column that doesn’t have a lot of different values, because the BTree would be optimised. But when it comes to the search, I’ve found that it’s not necessarly better than a BTree, probably because of the posting lists and posting trees that need to be fetched.

Here is the result of the same request for an integer with a BTree and with a GIN index. You can see that the times are almost the same.

I hope that this article helped you understand in which cases a GIN index can apply but why you should be careful about this index as updating it can be slow.